Turning back time with epigenetic clocks

A great way of thinking and questions about aging and epigenetics were just published by the author Liam Drew on Nature.

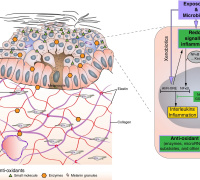

Biological age is an important concept, albeit a slippery one. Everyone's physical and mental functioning gradually declines from early adulthood onwards, but this occurs at different rates in different people. A technique for measuring biological age detects a signal that is a better guide to a person's functional capacity than their actual, chronological age.

As more and more scientists seek to slow, halt or rewind ageing, such methods will be needed to assess whether the new manipulations achieve these goals.

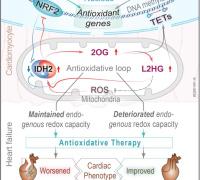

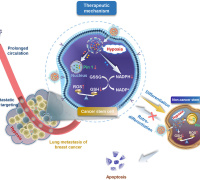

Epigenetic clocks use algorithms to calculate biological age on the basis of a read-out of the extent to which dozens or even hundreds of sites across an individual's genome are bound by methyl groups — a form of epigenetic modification.

In 2017, the scientists behind the growth-hormone trial — based at Intervene Immune, an anti-ageing biotech company in Torrance, California — were excited by their observation of thymus and immune renewal. They contacted Steve Horvath, an anti-ageing researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles, to ask if he would use an epigenetic clock to analyse blood samples they had taken during the trial. Horvath agreed. “Anybody who has an exciting study,” he says, “I love to get involved.”

But critics have questioned the purported decrease in biological age, stressing that it was a small, unblinded study with no placebo control arm. “If you have nine people,” says Horvath, “and you get a statistically significant result, it means there’s a strong effect.” He and the company are now running a randomized and placebo-controlled phase II replication on a larger group of 85 people.

The study is one of many, in humans and in animals, that seek ways to reduce epigenetic-clock scores — and thereby develop new anti-ageing interventions.

But some experts are concerned by the unknowns that still surround this technology. Matt Kaeberlein, who studies ageing at the University of Washington in Seattle, says: “It’s become a sort of dogma in the field — and in the popular perception — that these things are really measuring biological ageing. We really need to understand how these things are working.”

Horvath acknowledges this. “That’s the weakness of these biomarkers,” he says. “They come out of a machine-learning algorithm. They work beautifully in a mathematical sense, but biologists want more.”

The US Food and Drug Administration does not currently recognize epigenetic-clock scores as surrogate end points for clinical trials. It wants their mechanistic basis to be better defined. And it wants an answer to the crucial question of whether a short-term decrease in someone’s epigenetic-clock score definitively lowers their chances of developing age-related ill health.

Read more on this mind blowing point of view on aging for a better understanding of the biological clock. 10.1038/d41586-022-00077-8

Image Credits: Illustration- Sam Falconer

24th Annual ISANH Meeting

Paris Redox 2022 Congress

June 22-24, 2022 - Paris, France

www.isanh.net